Towards a Theory of Māori Vocal Music

- Amanda Riddell

.jpg/v1/fill/w_320,h_320/file.jpg)

- Sep 18

- 40 min read

Updated: Oct 24

Amanda Michelina (Ngāti Hikairo, Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Oneone)

This essay is the third in a series of essays on Māori music: https://www.amandamichelinasprogressiveparty.com/post/uneven-intervals-and-musical-hubs-a-comparative-study-of-m%C4%81ori-and-persian-traditions https://www.amandamichelinasprogressiveparty.com/post/mari-hamunata-and-the-hybrid-waiata-tradition

Introduction

The study of Māori music has too often been framed through analytical categories imported from Western musicology, especially the jargon of microtonality.

In much ethnomusicological literature, mōteatea, haka, and karanga are described as containing “quarter tones,” “inexact intonation,” or “sliding between notes,” with the implicit assumption that these practices are deviations from the supposedly stable framework of the equal-tempered scale.

Such approaches have the effect of othering Māori music, portraying it as imprecise or primitive when measured against the Western canon. This perspective not only distorts the lived reality of Māori musical expression but also imposes foreign theoretical models onto a tradition with its own internal logic.

The argument of this essay is that Māori music does not belong in the category of “microtonal” music as conventionally defined. Instead, Māori vocal traditions operate within a system of uneven intervals determined by affective states. In other words, intonation is not fixed to an abstract scale but emerges directly from the emotional and ritual context of performance. When one sings in grief (tangi), rage (riri), love or compassion (aroha), or mockery (whakatoi), the voice naturally assumes pitch shapes that embody those states. Affect itself is the code that generates intonation.

This is not imprecision but an alternative musical logic, one that places embodied emotion at the centre of pitch organisation.

This claim resonates strongly with comparative traditions. In Indian music, the śruti system divides the octave into twenty-two perceptible micro-intervals, each with a distinct emotional quality. In Persian music, uneven intervals of varying sizes form the building blocks of modal systems (dastgāh), with expressive significance attached to each. Chinese theory connected tonal systems with cosmic cycles, resisting equal temperament in order to preserve the natural correspondences between sound and the order of the heavens. In all of these cases, small differences of pitch carry great expressive meaning.

Alain Daniélou, in Music and the Power of Sound, argued that the equal-tempered scale mutilates every sound because it erases these differences, replacing natural ratios and expressive intervals with bland uniformity. Māori practice aligns with those non-Western systems in that intonation is inseparable from affect, and music is bound to cycles of time, ritual, and cosmology.

The essay will proceed by first situating Māori chant within the critique of equal temperament, drawing on Daniélou’s framework of natural correspondences.

It will then describe uneven intervals in Māori vocal traditions, arguing that they constitute affective codes that can be interpreted as modal frames. The principle of “affective intonation” will be developed and compared with both Eastern systems and Western performance practices such as method acting and musical theatre, where gesture and sound are likewise generated by emotion.

Daniélou’s shruti chart will be introduced as a comparative model, followed by an analysis of Persian uneven intervals (after Hormoz Farhat) and potential mapping onto Māori modes.

Finally, the essay will situate Māori practice within the broader Polynesian context, showing how cosmic cycles guide affect and intonation, and propose a new framework of notation capable of capturing this system without recourse to equal temperament.

By advancing this argument, the aim is to replace the language of microtonality with a framework grounded in affective intonation. In doing so, Māori music is re-theorised not as a deviation from Western norms, but as a coherent system of embodied knowledge that shares with other modal traditions a commitment to natural intervals, emotional resonance, and cosmic alignment.

1. Equal Temperament and the Erasure of Affect

The introduction of equal temperament in Europe marked one of the most consequential shifts in the history of musical tuning. Designed for the convenience of harmonic modulation and the expansion of tonal repertoire, it divides the octave into twelve equal semitones of one hundred cents each. This uniformity allowed composers to move freely between keys, particularly on fixed-pitch instruments such as the organ, harpsichord, and later the piano. Yet what was gained in harmonic versatility came at the expense of the fine gradations of pitch that give modal music its expressive depth.

Alain Daniélou, in Music and the Power of Sound, called equal temperament an “aberration that falsifies every interval and deprives music of its expressive qualities," effectively mutilating every sound. His argument was not merely about acoustics but about the destruction of music’s expressive grammar.

Natural intervals, derived from simple harmonic ratios such as 4/3, 5/4, and 9/8, carry distinct emotional resonances. A shift of even a few cents can change a phrase from compassionate to plaintive, or from triumphant to furious. In modal traditions across the world, these small shifts are the essence of musical affect.

Equal temperament, however, smooths them away. As Daniélou noted, “small differences of pitch bring about considerable differences in the expressive significance of the mode … in the tempered scale every chord beats.” What remains is a grid of abstract frequencies, mathematically efficient but emotionally impoverished.

This flattening has broader aesthetic and cultural implications. In Indian music, the śruti are valued for their affective weight; in Persian music, uneven intervals form the very building blocks of the dastgāh system; in Chinese music, tonal organisation was tied to cosmology, with theorists rejecting equal temperament repeatedly in order to preserve natural correspondences. Each of these traditions treats pitch as expressive substance rather than neutral measurement.

To impose equal temperament is to erase the grammar of emotion and the alignment of sound with ritual and cosmic cycles.

The consequences for Māori music are particularly acute. When mōteatea or karanga are analysed as “quarter-tone” or “microtonal” phenomena, they are implicitly measured against the tempered system. What is heard as deviation is in fact intentional affective inflection. A tangi’s descending cadences, a haka’s sharpened cries, or a karanga’s wavering high calls are not mistakes in pitch but deliberate enactments of grief, anger, compassion, or spiritual invocation. To reduce these to numerical “microtones” is to misinterpret them fundamentally.

It is here that the parallel with Daniélou’s critique becomes clearest. Equal temperament erases expressive nuance within European music itself, but when exported as an analytic framework it compounds the erasure by misrepresenting non-Western traditions. Māori music, far from being a flawed approximation of tempered scales, operates through affective codes that can be interpreted as modal frames.

These frames are not scales in the Western sense but systems of embodied knowledge, where intonation follows emotional and ritual logic rather than the dictates of an external tuning grid.

To develop a theory of Māori music, then, the first step is to reject equal temperament as the baseline of analysis. Only by setting aside the tempered ear can we begin to recognise the richness of uneven intervals and the way they encode affective states.

In this sense, Māori practice aligns with other modal systems across the world: it is not a deviation from universality but a living expression of the universal principle that intonation is guided by affect.

2. Uneven Intervals in Māori Tradition

Traditional Māori vocal performance — whether in the form of mōteatea (sung poetry), haka (dance-chant), or karanga (ceremonial call) — is characterised by a striking narrowness of melodic compass and a richness of intonational nuance.

Ethnomusicologists have often noted that many mōteatea fall within the range of a minor third (approximately 300–350 cents), sometimes expanding to a fourth or fifth in performance, but rarely beyond.

This compressed range does not signify musical limitation. Rather, it reflects a system in which expressive power is achieved not through wide melodic leaps but through subtle inflections of pitch, timbre, and contour. Within these narrow ranges, uneven intervals shaped by affect provide the true grammar of the music.

2.1 Tangi (lamentation)

Mōteatea associated with tangi often feature descending contours, wavering cadences, and a compressed intervallic space. The effect is one of contraction, mirroring the emotional and physical collapse of grief.

The voice may shade a minor second (≈ 90 cents) against a neutral tone (≈ 135 cents), producing an intonational step that hovers around 225 cents — narrower than the tempered minor third.

These uneven steps embody the affect of mourning; they are not arbitrary “microtones” but signs of sorrow coded in sound.

2.2 Riri (anger, defiance, pride)

In haka performed in contexts of war, defiance, or assertion of mana, the intonational logic shifts. Here we find sharpened pitches and expanded intervals, sometimes approaching 364 cents (≈ 160 + 204), wider than the tempered minor third.

The effect is piercing, aggressive, and confrontational. The raised cries of haka riri are not “out of tune” but deliberately stretched to convey fury and strength. The mode of riri is expansive, outward-thrusting, and emphatic.

2.3 Aroha (compassion, longing)

Karanga and waiata aroha often inhabit a sound world of hovering intervals, with the voice oscillating around a neutral tone of 135–160 cents. These intervals resist closure; the sound is suspended, yearning, stretching towards something unattainable.

The affect is one of compassion and longing, enacted not by text alone but by the pitch contour itself. To sing aroha is to allow the voice to linger in this unstable tonal space, neither collapsing like tangi nor projecting force like riri.

2.4 Whakatoi (mockery, playfulness)

In haka and chants of ridicule, the intonational palette includes exaggerated leaps and unstable fluctuations. Here, intervals may stretch toward the “plus tone” of ≈ 270 cents, destabilising the otherwise narrow modal space.

The mocking tone of whakatoi arises from the deliberate distortion of contour: sudden rises, unstable cadences, and ironic exaggeration. Once again, the affect dictates the intonation, producing a mode of derision and humour.

2.5 Modal Frames of Affect

What emerges from these examples is a set of affective modes, each with its own characteristic intervallic pattern:

Tangi: compressed, descending intervals (≈ 90c + 135c).

Riri: expanded, sharp intervals (≈ 160c + 204c).

Aroha: suspended neutral tones (≈ 135–160c oscillations).

Whakatoi: exaggerated plus tones (≈ 270c leaps).

Though all remain within the narrow compass of a minor third, the modal colour of each chant derives from which uneven intervals are selected and how they are inflected. This produces a framework that can be legitimately described as modal, not in the sense of major and minor scales, but in the sense of expressive frames tied to emotional and ritual purpose.

A useful parallel comes from the Persian dastgāh system, as analysed by Hormoz Farhat. Persian classical music does not rely on fixed scales but on collections of uneven intervals — the minor second (≈ 90c), small neutral (≈ 135c), large neutral (≈ 160c), whole tone (≈ 204c), and plus tone (≈ 270c). Each dastgāh is built from different combinations of these steps, producing distinct affective identities: solemnity in Dastgāh-e Shur, exaltation in Dastgāh-e Mahur, or mystical yearning in Dastgāh-e Segah.

What differentiates these modes is not range alone but the emotive power of interval choice and emphasis. Māori practice, though not codified in theoretical treatises, functions in a strikingly similar way. The affective state determines which uneven intervals are foregrounded, compressing them in laments, expanding them in haka, suspending them in karanga, or destabilising them in mocking chants.

Like dastgāh, Māori modes rely on expressive differentiation through interval-class selection within a relatively narrow compass. Where Persian musicians might identify a mode by its intervallic skeleton, Māori performers recognise it through affective and ritual cues — grief, anger, compassion, derision — which then generate the intonational frame.

In both traditions, then, modal identity arises not from abstract scale-structures but from affect embodied in uneven intervals. Persian theory has preserved this in systematic notation and pedagogy, while Māori tradition has encoded it in performance practice and oral transmission. Both approaches point to a universal principle: modes are affective frames, not fixed collections of notes.

3. Affective Intonation as a Universal Principle

If Māori uneven intervals can be understood as affective modal frames, then they form part of a wider human pattern: the organisation of sound by emotion rather than by abstract tonal grids. This principle is most clearly articulated in the classical systems of South and West Asia, but it is also evident in Western performance practice once we look beyond the strictures of tempered scales.

3.1 Indian Śruti and Emotional Colour

In Indian music, the octave is divided into twenty-two śruti, perceptible micro-intervals that carry distinct affective qualities. Daniélou’s chart maps them not simply as measurements but as emotional categories: compassion, pathos, wrath, marvel, softness, love.

A rāga is not merely a collection of notes but a mode of feeling: dawn rāgas evoke serenity through rising contours, evening rāgas arouse longing through falling cadences. Here, intonation is inseparable from affect. A rāga without its prescribed affect is considered incomplete, or even broken.

3.2 Persian Dastgāh and Expressive Intervals

As Farhat’s analysis demonstrates, Persian classical music relies on a small set of uneven intervals, approximately measured as the minor second (~90c), small neutral (~135c), large neutral (~160c), whole tone (~204c), and plus tone (~270c). Each dastgāh is defined not by a fixed scale but by the affective character of its chosen intervals. Dastgāh-e Shur conveys solemnity, Mahur radiates grandeur, Segah suggests mystical yearning. The identity of a mode lies in the emotional shading of its intervals, not in any abstracted tuning system.

3.3 Māori Affective Modes

Māori modes operate on the same principle. Tangi compresses intervals into a descending, sorrowful frame; riri expands them into sharp, forceful cries; aroha suspends them in neutral oscillation; whakatoi exaggerates them into mocking leaps.

The identity of each is not notational but affective. Just as a rāga is defined by its rasa (essence of emotion), a Māori chant is defined by its affective state, which dictates the intervallic choices of the performer.

This is plain in existing categorisations: https://teara.govt.nz/en/traditional-maori-songs-waiata-tawhito/page-3

3.4 A Western Analogy: Method Acting and Musical Theatre

For Western readers, an accessible analogy lies in method acting and musical theatre. In these traditions, gesture, posture, and vocal delivery are driven by the emotional state of the character. An actor does not calculate intonation mathematically; grief draws the voice downward, joy expands the chest and brightens the timbre, anger sharpens the tone and accelerates the rhythm.

In musicals, these emotional cues are codified into recurring performance conventions, so that audiences can immediately interpret vocal gesture as emotional state.

Māori affective intonation works in the same way. A performer who enters the state of tangi will naturally produce descending, wavering intervals, just as an actor embodying grief will slump and drop their voice. Affect is not an overlay on intonation — it is the generative code. This is why Māori music does not require external theoretical charts: the body itself, in states of ritual emotion, generates the necessary intervallic patterns.

3.5 The Universal Principle

From India’s śruti to Persia’s dastgāh, from Māori chant to Western stage performance, a universal principle emerges: intonation follows affect. Equal temperament is the historical anomaly, replacing the expressive logic of affective intonation with abstract uniformity. Māori music thus aligns with a global tradition of modal systems that ground themselves not in mathematical convenience but in the lived experience of emotion, ritual, and cosmology.

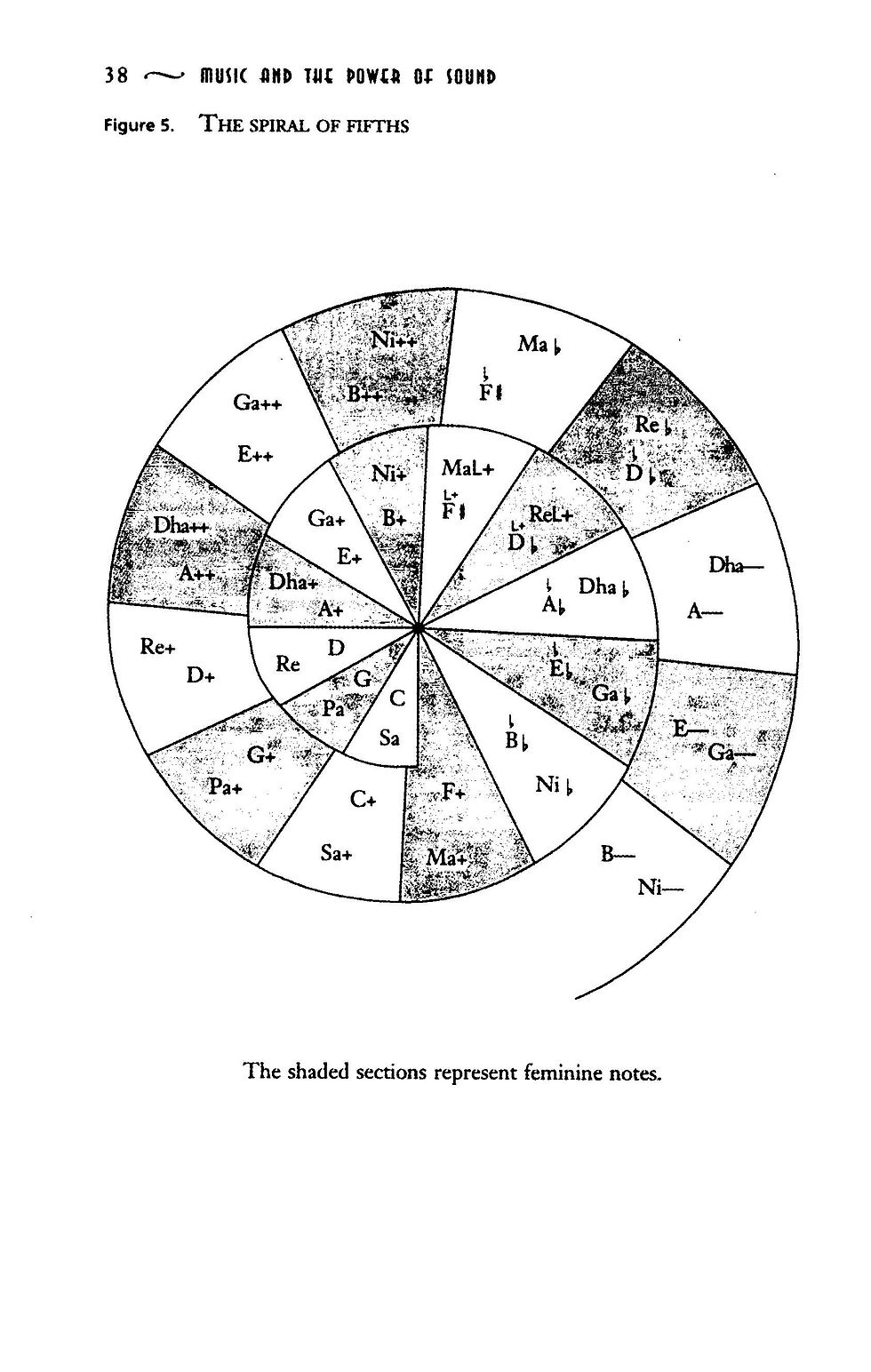

4. Daniélou’s Shruti Chart

One of the most compelling comparative tools for understanding affective intonation comes from Alain Daniélou’s presentation of the śruti system in Music and the Power of Sound. In his reconstruction of ancient Indian theory, the octave is divided not into twelve equal semitones but into twenty-two distinct śruti, each with its own expressive resonance.

Daniélou emphasises that these intervals are not mathematical abstractions but emotional categories: each śruti corresponds to a particular affective quality, a mood or rasa that governs its role in performance.

4.1 The Chart of 22 Shruti

Daniélou’s chart arranges the śruti alongside their emotional qualities. For instance:

Tīvrā, Dīpta, Raudrī – marvelous, heroic, furious

Mṛdu, Rati, Prīti – love, tenderness, softness

Dayāvatī, Karuṇā, Madantī – compassion, pathos, grief

Āyata, Krodha – comic, wrathful

Mādhya, Rañjanī – moderate, balanced

The point is not the exact measurement of these intervals but their expressive utility. A rāga that requires pathos will favour the śruti aligned with grief, while one aiming for grandeur will select those aligned with heroism or marvel. The śruti chart is thus a map of affect into sound, a framework where intonation is inseparable from emotional force.

4.2 Affective Equivalence in Māori Music

When viewed through Daniélou’s lens, Māori uneven intervals function in a strikingly similar way. A tangi chant, with its compressed descent, occupies the same affective space as the śruti of compassion and grief. A haka riri, with its stretched neutral tones and piercing cries, corresponds to the śruti of wrath and heroism.

A karanga aroha resonates with the śruti of tenderness and longing.

A haka whakatoi invokes the comic exaggerations aligned with āyata.

In other words, while Māori practice does not enumerate its intervals into twenty-two named categories, the principle is the same: intervals are chosen according to affect, and affect is understood as an intrinsic, universal property of sound.

4.3 Shruti and Universality

Daniélou argued that the universality of these affective correspondences is obscured by equal temperament. Once intervals are forced into twelve equal steps, the subtleties that differentiate love from compassion, or anger from pride, are lost. The system may be efficient for harmonic modulation, but it is destructive to modal expression.

Māori practice, like Indian practice, preserves these subtleties by allowing pitch to move freely according to affect, rather than by confining it to an equal-tempered grid.

4.4 Toward a Comparative Framework

Placing Daniélou’s shruti chart alongside Māori affective modes allows us to see them as parallel systems of modal expression.

Where Indian theory catalogues twenty-two categories, Māori practice operates with embodied categories of grief, anger, compassion, and mockery.

Both systems demonstrate that intonation is never neutral: every note is charged with emotional significance. Both also show that modes are not abstract pitch collections but emotive frames that shape the performance of sound in ritual and social life.

5. Comparative Intervals and Māori Affective Modes

To satisfy those who prefer numerical description, it is possible to draw on Persian modal theory to provide approximate cent values for uneven intervals. Hormoz Farhat identifies five characteristic steps that form the building blocks of the dastgāh system:

Minor second (m): ~90 cents

Small neutral tone (n): ~135 cents

Large neutral tone (N): ~160 cents

Whole tone (M): ~204 cents

Plus tone (P): ~270 cents

Amanda Michelina: For those who are wondering how I decoded the tapa circle, consider the nucleus circle as Oro-Tihi tuatoru-Tihi hauaura-Tihi nui, then imagine the uneven lines between the first and second circles as representations of Farhat steps. The middle circle of shaded touching triangles represents the notes, much like the derived microtones from a Farhat-based mode. Shaded tirangles are strong notes, unshaded ones are weaker tones. To find the microtones, take the first step of the enharmonic and then listen for the smaller notes between it and the first Tihi, then find the distances between each of these tones, remove the duplicates and place them in order from lowest to highest, with the Farhat step as the highest. This pattern remains consistent, and isn't designed to coincide with the enharmonic, but with the real notes pitched using that enharmonic as guide.

The compass is pointing towards a slightly flat starting note, which then moves up a microtone or two to the anchor note. This is representative of the 'false start' that is often audible in Polynesian songs.

The steadier intervals (90c, 204c) are given with narrower beams, suggesting less oscillation between the tones, and the second group of encircled triangles appear to be saying where the note goes, as opposed to the scale degree, which can be the note, but isn't always. The triangles with the straight lines between the second and third circles represent the pure harmonics, with the strongest ones coinciding with the external triangles - the world outside one's self - and drawn with thicker lines. The lines between them represent the real distance between the notes, much in the way that I derived the maramataka microtones from the distance between Farhat's steps, and there's notable disjunctions where there is no connecting line, which map to the Oro-Tihi model from Māori music. Think of this circle as using a map of cosmic correspondences to demonstrate how notes emanate from the body on a raft of cultural frequencies derived from nature.

Farhat Steps as Core Anchors

The Farhat steps — 90c, 135c, 160c, 204c, 270c — are the primary anchor points of the Māori mōteatea span. These intervals, mapped between Oro and Tihi, form the structural backbone of chant. They are not evenly spaced, but irregular markers that singers recognise as stable tonal poles.

Against this uneven backbone lies a secondary system: a lattice of thirteen 90-cent divisions per octave, each subdivided into minor quarter tones (~25c, 45c, 60c).

This lattice is not the foundation but the field of motion through which singers travel between Farhat anchors. It provides the flickering effect, the sense of tonal shimmer that makes mōteatea distinct.

The relationship is therefore hierarchical:

Oro and Tihi frame the span.

Farhat steps provide the core anchor points within that frame.

Minor quarter tones create texture, inflection, and spiritual depth as singers move between anchors.

In this way, Māori vocal music resembles the Indian shruti system: stable modal anchors surrounded by dense microtonal inflections. Yet the Māori model is distinctive in its cosmological underpinning — the lattice steps resonate with the lunar maramataka cycle, while the flickering minor quarter tones embody the shifting qualities of its nights.

The Comma and the Imperfection of Scales

Alain Daniélou reminds us that no tuning system closes perfectly: twelve fifths do not return exactly to the octave, but leave a tiny remainder — the comma. This imperfection, he argues, is fundamental: if the world were mathematically perfect, it would collapse into stillness. Instead, the comma represents “the essential difference between what is finite and what is infinite,” the spiral gap that keeps cycles alive.

In the Māori 13-step system, the same principle emerges. Dividing the octave into thirteen spans of ninety cents, plus the Farhat steps from the twelfth step, leaves a comma at the end — a small remainder that prevents closure. Rather than undermining the system, this imperfection is its strength. It parallels the mismatch between lunar and solar calendars in the maramataka: the lunar year does not fit neatly into the solar year, and it is this gap that generates the rhythms of planting, tides, and ritual life.

Thus, the 13-step scale mirrors the cosmos:

Farhat steps provide the core anchor points of the mōteatea span.

Oro and Tihi mark the poles, grounding the voice.

Minor quarter tones within the maramataka frame create flicker and movement.

And the comma at the octave embodies the necessary imperfection that links the musical system to the cycles of time and existence itself.

Rather than an error, the comma is a spiritual hinge — the small difference that allows the cycle to continue, ensuring music, like the world, remains dynamic, alive, and open.

Principle: Oscillatory Harmony Harmony in the maramataka frame does not arise from fixed tempered chords, but from the oscillation between adjacent commatic ratios (≈ 25–90¢). When singers or instruments shift between ratios such as 36/35 (~49¢), 81/80 (~22¢), 128/125 (~41¢), and 256/243 (~90¢), the ear perceives a field of beating, shimmer, and resolution.

Relational basis: These oscillations are grounded in small-integer frequency ratios, producing consonant beating when aligned and expressive dissonance when in flux.

Temporal quality: Harmony is not vertical but temporal — it emerges over time through the wavering and return between steps.

Cycle connection: Because the steps do not sum neatly to an octave, repeated oscillations create commatic drift, mirroring the imperfect closure of natural cycles such as the maramataka lunar calendar.

Aesthetic effect: The “harmony” is the living resonance of these oscillations — a shimmer rather than a static chord, evoking natural processes like the waxing and waning of the moon or the restless motion of the sea.

These steps are not combined into fixed scales but used flexibly to create modal colouration. Different dastgāh are distinguished by the choice of intervals, their ordering, and their affective charge.

5.1 Mapping Persian Intervals to Māori Affective Modes

Although Māori tradition does not name or quantify intervals, its affective modes can be described in comparable terms. The following table juxtaposes Farhat’s Persian values with Māori affective states:

Interval Type (Persian) | Value (approx. cents) | Use in Persian Modes (Farhat) | Māori Affective Mapping | Example Māori Context |

Minor second (m) | ~90c | Pathos, tension, compression | Tangi – grief, mourning | Descending slides in mōteatea tangi |

Small neutral tone (n) | ~135c | Ambiguity, longing | Aroha – compassion, yearning | Hovering oscillations in karanga aroha |

Large neutral tone (N) | ~160c | Tension before release | Riri – anger, pride | Sharp cries in haka riri |

Whole tone (M) | ~204c | Stability, balance | Whakatau – equilibrium | Steady steps in commemorative mōteatea |

Plus tone (P) | ~270c | Dramatic leap, emphasis | Whakatoi – mockery, exaggeration | Exaggerated rises in mocking haka |

Remember that these intervals can be placed in different orders, particularly as the microtones are derived from the first step of the enharmonic and the relationship between that Farhat step and the Tihi point.

This mapping is approximate, but it illustrates that Māori modes occupy the same expressive field as Persian ones. Both rely on uneven steps smaller or larger than the tempered semitone or tone, and both encode affect in their intervallic choices.

5.2 Modal Frames Within a Narrow Compass

The crucial difference is that Māori chants typically remain within a compass of a minor third (≈ 300–350 cents). The modal colour emerges not from wide-ranging melodies but from different combinations of uneven steps within that narrow space:

Tangi compresses the span: ~90c + 135c = 225c.

Riri expands it: ~160c + 204c = 364c.

Aroha oscillates in the ambiguous space of 135–160c.

Whakatoi destabilises the frame with leaps of ~270c + 204c.

Just as dastgāh differentiates its expressive modes by intervallic emphasis, Māori tradition differentiates affective states by selecting and combining uneven steps in specific ways. Amanda Michelina: One important difference is that Māori notes are measured by the oro matua, rather than relative between notes, as the Persian dastgāh are. Hence, a mōteatea may include a phrase that sounds like shifting between 2-3 or 3-4 in Farhat's chart, as it's actually two intervals that are tied to the ground. This is why I've described them as chess moves, rather than a 'scale' or 'mode' - they're a grammar, not a sentence. For example, the plus tone is likely the note that extends the compass towards a fourth or fifth, while the Farhat tones sound equivalent to a Māori scale as defined by default traditional chants.

5.3 Toward a Shared Language of Affect

What this comparison shows is that Māori music, like Persian music, is governed by modal affect rather than equal-tempered measurement. The numbers are useful for cross-cultural dialogue, but they should not obscure the fact that for both systems, intonation is inseparable from emotion. Modes are not abstract collections of notes but embodied frames of affective knowledge, lived in performance and ritual.

5.4 Just Intonation and Māori Vocal Practice

It is worth noting that the aggregate intervals we have been discussing — 90c, 135c, 160c, 204c, and 270c above the tonic — correspond closely to simple frequency ratios found in Just Intonation (JI). For example, 90c aligns with the limma (256:243), 135c with the small neutral step (27:25), 160c with the wider neutral (11:10), 204c with the whole tone (9:8), and 270c with the septimal minor third (7:6). Each of these values is within a few cents of a low-complexity JI ratio.

This is significant for two reasons. First, it suggests that Māori vocal practice is not “inexact” or “sliding” in a random way, as older ethnomusicological accounts implied, but is instead grounded in acoustically natural relationships that singers reproduce aurally.

Second, JI can be seen as a kind of cultural constant: traditions as diverse as Persian dastgāh, Indian rāga, Gregorian chant, and Polynesian mōteatea converge on similar interval sizes because they emerge directly from the harmonic series.

Thus, Māori affective intonation may be understood as a culturally specific expression of these universal harmonic tendencies. What differentiates Māori practice is not the absence of structure, but the way these intervals are mobilised within oro and the emotional frames of tangi, riri, aroha, whakatoi, and others.

Māori singers and audiences hear these tones as entirely natural and internally coherent. Describing them in terms of JI, rather than as deviations from the tempered scale, affirms both their precision and their expressive power.

5.4 Tohunga Methods and the Formality of Oro

In considering whether Māori musical practice ever acknowledged something akin to "notes," the role of tohunga provides important context. Tohunga, as ritual experts and guardians of karakia and mōteatea, were not only custodians of words but also of sound itself. Their training in whare wānanga involved strict transmission of vocal methods: how to shape breath, how to maintain resonance, and how to intone chants correctly so that they carried spiritual efficacy.

Ethnographic descriptions suggest that tohunga chants operated within a narrow pitch compass, centred around what could be described as a tonal anchor. Here the concept of oro matua becomes especially relevant. Oro matua refers to a "home sound," a central pitch that grounds the vocal delivery. While this was not conceptualised in terms of a Western tonal centre like C or G, it represented an acknowledgement that chants had to be anchored in a specific reference pitch.

This indicates that tohunga practice did involve a kind of formal recognition of pitch accuracy. If a karakia was performed with incorrect intonation, it risked being ineffective or spiritually dangerous. Apprentices were corrected until their intonation matched the required form, which implies that while no written notation system existed, there was nevertheless a formal system of preserving and transmitting pitch relationships.

In this sense, tohunga methods overlap strongly with the idea of affect intonation. The manipulation of contour, microtonal shading, and glissandi served not just musical but spiritual functions.

The emotional force of a chant was inseparable from its tonal correctness, and this correctness was preserved as rigorously as the words themselves. The formalisation lay in oral discipline rather than written symbols, but the existence of concepts such as oro matua shows that Māori did, at some level, theorise sound in terms of reference points and pitch classes.

6. Polynesian Context and Cosmic Cycles

The affective intonation of Māori chant is not an isolated phenomenon but part of a wider Polynesian system in which music, ritual, and cosmology are tightly intertwined. Across Oceania, performance traditions are embedded within temporal cycles of stars, moon, and seasons.

Just as Indian rāgas are assigned to times of day, and Chinese tonal systems were linked to cosmological measures of the calendar, Polynesian musics align vocal expression with the rhythms of the cosmos.

6.1 Navigation Chants and Star Lines

In Hawai‘i, Tahiti, Satawal, and other island groups, chants preserved as part of wayfinding practice encode star paths. These chants list stars in rising and setting order, often accompanied by rhythmic intonation that aids memorisation.

The chant itself is a mnemonic device, but it is also a performance: rhythm and contour mirror the sequence of stars, allowing navigators to internalise astronomical cycles. The music is not merely descriptive but participatory — it draws the performer into the cosmic order through embodied sound.

6.2 Seasonal and Ritual Timing

Elsewhere in Polynesia, song and chant are linked to agricultural and ritual calendars.

In the Marquesas, pehe song forms are tied to particular ceremonies, many of which coincide with seasonal events such as the return of migratory birds or the appearance of specific constellations.

In Tahiti, Tupaia and his contemporaries were trained in chants that carried star lore and sailing instructions, performed at the correct season for voyaging.

The alignment of chant with celestial timing reinforced the understanding that music was not an arbitrary activity but a cosmological act, harmonising human life with the order of the heavens.

That's where those Farhat steps and clusters might be helpful.

6.3 Hawaiian Mele and Moon Phases

Hawaiian mele and oli provide especially clear evidence of intonational practice aligned with temporal cycles. Certain chants are performed at dawn, their contours rising with the light, continuing the cycle through daytime chants with steadier contours, and ending with evening or nocturnal chants marked by descending gestures.

Similarly, chants associated with moonlit nights (po mahina) were intoned with hovering or shimmering effects, designed to echo the lunar ambience. It has been argued that the origins of Hawaiian music can be found in the sounds of nature (ahupuaʻa) and that hearing these sounds inspired the development of musical culture.

In all cases, the affective quality of the chant is inseparable from the cosmic time of its performance.

Hawaiian language poet and scholar Larry Kimura has said that "Ua like ke mele Hawaiʻi kuʻuna me ke kino kanaka. Ua hiki ke māhele ʻia ke mele i loko o ʻelua māhele nui aʻu e kapa nei, ʻo ia ke kino ʻiʻo a me ke kino iwi (Donaghy 2013)."

[Traditional Hawaiian songs are like the human body. You can divide them into two major categories that I will define as the flesh of the body and the bones of the body.]

This quality of describing song through physical qualities goes to the heart of what affective intonation really means. The song is part of the body, which is part of the cosmic cycle, and the intonation is defined by tinana, rather than abstract notation.

6.4 Māori Maramataka and Matariki

Within Aotearoa, these principles were also active. The maramataka, or lunar calendar, structured daily and seasonal rhythms, guiding planting, fishing, and ritual activities. Certain nights of the moon were considered auspicious for particular chants or ceremonies, and vocal delivery reflected the mood of the occasion.

The heliacal rising of Matariki (the Pleiades) marked the Māori New Year, accompanied by chants of remembrance and renewal. These chants carried upward inflections and bright timbres, enacting a return of vitality to the land and people.

Conversely, funeral tangi aligned with the night, employing descending intonations that resonated with darkness and loss.

6.5 Affect as Cosmic Code

When viewed together, Polynesian traditions reveal a consistent logic: cosmic cycles set the affective frame, and affect determines intonation. Navigation chants translate star risings into musical order; seasonal chants embody agricultural and celestial rhythms; dawn and night chants mirror the daily cycle of light.

Māori practice belongs to this system, where the body’s intonation is not only an expression of individual emotion but also a reflection of the larger cosmic pattern.

6.6 Toward a Comparative Understanding

By situating Māori chant in this broader Polynesian context, we can see that its affective modes are not arbitrary or culturally isolated. They are variations on a pan-Polynesian principle: that music mediates between human and cosmos, with intonation functioning as the bridge. Just as Indian rāgas align emotion with time of day, and Chinese tonal systems with seasonal cycles, Polynesian chant demonstrates a cosmic modality — one in which the universe itself dictates which affect is appropriate, and therefore which intervals are chosen.

6.7 Rhythm, Percussion, and the Intersubjective Musicality Principle

Colwyn Trevarthen’s Intersubjective Musicality Principle (IMP) proposes that human beings are predisposed to coordinate with one another through rhythmic, affective gestures — from infant-caregiver exchanges to music and dance. This principle aligns with the argument of affective intonation: emotion generates contour, and rhythm is the medium through which bodies synchronise that emotion across a group.

In Polynesia, rhythm often functions as the scaffolding for pitch. While many traditions are described as “monotone” or “narrow-ranged,” it is rhythm that provides the structure within which subtle intonational differences acquire meaning. Percussive instruments — slit drums, stamping tubes, pahu, or even hand-clapping — establish a pulse that allows singers to place uneven intervals with shared accuracy. In performance contexts such as haka, the body itself becomes percussion: foot-stamping, chest-slapping, and breath rhythms regulate vocal delivery.

This rhythmic framework may have served a dual function:

Temporal alignment – ensuring that group performers intone together despite the fluidity of pitch.

Affective anchoring – linking specific rhythmic gestures to emotional states, which in turn shape intonation. For example, the accelerating pulse of haka riri amplifies anger, pulling intonation upward into piercing cries; the slow, rocking rhythm of tangi supports descending contours of grief.

Polynesian traditions thus embody Trevarthen’s IMP at the collective level: rhythm is not merely background but a social technology for synchronising affect and intonation. Where Daniélou emphasised the natural correspondences of intervals, Trevarthen reminds us that these correspondences are realised intersubjectively — through shared movement, rhythm, and voice.

6.8 Farhat’s Steps, Trevarthen’s Gestures, and Mithen’s Evolutionary Model

Farhat’s five characteristic intervals — approximately 90c, 135c, 160c, 204c, and 270c — can be understood not simply as “microtonal notes,” but as codified gestures within human vocal communication. In Māori tradition, these steps are selected relative to the oro anchor to embody affect: compressed for tangi (lament), expanded for riri (anger/defiance), and so forth.

This flexibility resonates strongly with Trevarthen’s models of intersubjective musicality, which identify the same contour types in infant–mother communication. Small pitch flicks serve as attention-getters, mid-sized steps regulate conversational turns, and larger arcs convey powerful emotions.

Mothers’ nursery songs illustrate the biological foundation of this system. Cross-cultural evidence shows that lullabies and play songs typically fall within a range of a minor third to a perfect fourth (≈ 250–500 cents). Within that span, the minor third (270c) — identical to Farhat’s largest step — frequently functions as the ceiling of emotional expressivity.

Smaller intervals cycle repeatedly, while the occasional leap into the upper register punctuates and intensifies meaning. Trevarthen demonstrated that these contours mirror hand, head, and body gestures: rises coincide with reaching or expanding, falls with closure or settling.

Steven Mithen’s The Singing Neanderthal (2005) provides the evolutionary frame that binds these observations together. He proposed an early communicative system, which he termed “Hmmmmm” (holistic, manipulative, multimodal, musical, mimetic), in which humans and Neanderthals relied on precisely these kinds of affective pitch contours and gestures to convey emotion and coordinate group life. What Trevarthen observes in the nursery, and what Farhat maps through interval analysis, Mithen situates in deep time: the Hmmmmm system is the prehistoric matrix from which both music and language later diverged.

In this light, Māori vocal practice may be viewed as a living continuation of an ancient communicative heritage. The oro functions as the stabilizing ground, while the Farhat steps encode a palette of affective gestures with roots stretching back to the earliest forms of human musicality. Trevarthen’s infant studies show how these gestures remain foundational to human development, while Mithen’s evolutionary account underscores their antiquity and universality. Together, they reveal that what might otherwise be dismissed as “inexact intonation” or “quarter tones” is better understood as a biologically and historically grounded gestural language, preserved and ritualized in Māori song.

Comparative Chart

Interval (Farhat) | Size (cents) | Māori Function | Trevarthen Gesture Equivalent | Mithen / Evolutionary Role | Nursery Song Evidence |

Small flick | ~90c | Subtle tonal bend, preparatory note | Eyebrow lift, questioning tone, “flick” gesture | Attention-getting, directional signalling in Hmmmmm | Micro-rises in infant-directed speech, soothing murmurs |

Gentle incline | ~135c | Linking step between phrases | Hand tilt, conversational prosody | Regulating turn-taking, coordinating group response | Common in playful rhymes and teasing inflections |

Mid-step (lower) | ~160c | Emotional colour, shifting emphasis | Clear rise/fall in speech melody | Core prosody of Hmmmmm; emotional shading | Frequent in lullabies as “comfort” contour |

Mid-step (upper) | ~204c | Assertive gesture, emphatic closure | Gesture arc with arm/head movement | Emphatic signalling in group calls | Often appears in nursery songs’ climactic syllables |

Large arc | ~270c (≈ m3) | Climax of tangi wail, riri peak | Full-body gesture, reaching or expansive cry | Core expressive span of Hmmmmm, high-emotion communication | Upper limit of lullaby/play-song range (≈ m3–P4) |

6.9 Oro, Uneven Steps, and Glissandi Across Polynesian Music

The oro + uneven steps model, developed from close analysis of Māori mōteatea and ritual chant, offers a compelling framework for understanding other Polynesian musical traditions. While the specific terminology of oro is particular to Māori, the underlying principle of an anchoring pitch around which singers gravitate is widespread across Polynesia. This anchor does not function like the “tonic” of a Western scale, fixed and tempered, but rather as a centre of gravity: a point of return that organizes melodic motion, establishes emotional grounding, and unifies group performance.

Across Polynesia, movement away from this anchor is seldom regularized into equal steps. Instead, singers employ uneven intervallic motion, selecting smaller or larger steps according to context and affect. These steps are often flexible in size: compressed in laments, expanded in war chants or ritual declarations. The logic here is affective rather than mathematical, aligning with the gestural models observed in both infant–mother communication and evolutionary accounts of early human musicality.

A key feature that reinforces this uneven system is the pervasive use of glissandi. Sliding between anchor points is not simply ornamentation but a structural element of Polynesian performance practice. In Hawaiian mele, singers frequently glide into and out of “fixed” notes, blurring the boundaries of the pentatonic frameworks that outside analysts often impose.

In Tongan and Samoan choral traditions, voices enter pitches by sliding together, producing momentary clashes that resolve into resonant blends — an effect that is both expressive and socially cohesive. In Tahitian and Marquesan chants, cadences are commonly marked by downward slides, reinforcing the sense of closure through motion rather than fixed scale degree.

Taken together, these features suggest that Polynesian musics share a modal logic distinct from the scalar dichotomies of East Asia or Europe. Rather than being defined by the presence or absence of particular scale tones (major vs. minor pentatonic, diatonic vs. chromatic), Polynesian traditions are organized by anchoring tones, uneven step sizes, and glissando transitions. This triad of principles provides a more accurate description of their sonic reality than the categories imposed by Western notation.

It also reframes what earlier ethnomusicologists dismissed as “inexact intonation” into a positive, structured system of affective communication, consistent across the Polynesian world while allowing for local variation in style and performance context. 7. Towards a Notational Framework

One of the most persistent challenges in the study of Māori music is the question of notation. Western staff notation, designed for equal-tempered scales and harmonic progression, is profoundly unsuited to capturing the subtleties of affective intonation.

When applied to mōteatea, haka, or karanga, staff notation forces fluid intervals into discrete semitone boxes, reducing intentional affective inflections to apparent “mistunings.” The result is a distortion: what is living and embodied in performance becomes flattened on the page.

7.1 The Limits of Staff Notation

Staff notation presumes fixed pitch values, equal spacing of intervals, and a directional logic toward harmonic cadence. None of these assumptions holds in Māori practice.

Vocal lines hover within a narrow range, slide continuously between pitches, and resist closure in favour of affective contour. Attempting to represent these features with accidentals (e.g., “quarter-tone flats”) or dotted slurs obscures the fact that affect itself generates the contour.

Notation in this sense becomes a straitjacket, forcing Māori performance into categories foreign to its logic.

7.2 Alternative Models from Comparative Traditions

Other traditions that prioritise modal intonation have also struggled with staff notation. Indian music is often represented by cipher notation that records contour rather than absolute pitch.

Persian music uses simplified staff with annotations for neutral intervals. Contemporary graphic scores in Western avant-garde traditions have moved toward shape, gesture, and proportional spacing to capture sonic qualities beyond the tempered scale. These approaches suggest that notation should be adapted to the expressive needs of the music, not imposed as a universal standard.

7.3 Graphic Contour Notation for Māori Music

A promising direction is the development of graphic contour notation, designed specifically for Māori contexts. Such a system would employ five basic registers — high, middle, and low — rather than a fixed tempered staff. Within each register, lines and symbols could depict rising, falling, hovering, or exaggerated contours. Instead of sharp and flat symbols, notation would mark affective states: tangi (grief), riri (anger), aroha (compassion), whakatoi (mockery).

The performer, guided by affective annotation, would reproduce the corresponding intonational tendencies.

7.4 Culturally Resonant Symbols

For this system to be meaningful, it must draw on Māori visual traditions. Koru spirals could represent descending and contracting motions; tukutuku patterns could mark repeated oscillations; weaving motifs could symbolise intertwining voices or overlapping phrases. Such symbols not only capture contour but embed notation in Māori cosmology, linking visual and aural art forms. This approach would echo the way carving, weaving, and tattoo embody genealogical and cosmological knowledge, extending into the realm of musical transcription.

7.5 Benefits and Challenges

The benefit of such a system would be twofold: it would free Māori music from the distortions of staff notation and would provide a culturally grounded way of documenting performance for teaching, preservation, and analysis.

The challenge lies in balancing specificity with flexibility. Too rigid a system risks freezing affect into static symbols, undermining its embodied nature.

Too loose a system risks ambiguity, making transcription useless for pedagogy.

The solution may be to design a layered system: contour graphics for general shape, affective symbols for emotional code, and cent approximations for cross-cultural dialogue.

8. Implications

The recognition of Māori music as an affective-intonational system has implications that extend far beyond the technicalities of pitch measurement. It reshapes how Māori traditions are understood within ethnomusicology, how they are transmitted within communities, and how they are situated within the wider global history of modal music.

8.1 Reframing Māori Music in Ethnomusicology

For decades, the description of Māori chant as “microtonal” has served to marginalise it, casting it as a deviation from European norms rather than as a coherent system in its own right.

By understanding uneven intervals as affective codes that can be interpreted as modal frames, Māori music is no longer reduced to a curiosity of pitch.

Instead, it takes its place alongside the great modal systems of the world — Indian rāga, Persian dastgāh, Chinese lǜ — as a tradition that encodes emotion, cosmology, and social meaning into sound.

8.2 Transmission and Pedagogy

This framework also has consequences for teaching and preserving Māori music. If intonation is affect-driven, then pedagogy must emphasise embodied states rather than fixed scales. Learning mōteatea or karanga is not about memorising notes but about entering the affective space of tangi, aroha, or riri.

A graphic-notation system that encodes contour and affect could complement oral transmission, providing a tool for younger generations without undermining the primacy of embodied practice. Such an approach would bridge traditional pedagogy with contemporary documentation needs.

8.3 Decolonising Analysis

Replacing the language of microtonality with affective intonation also contributes to the decolonisation of analysis. It challenges the imposition of Western categories that obscure rather than illuminate Indigenous practice. Instead of treating Māori music as a deficient version of European tuning, we begin from Māori categories — affect, ritual, cosmology — and interpret intonation through those.

This not only does justice to Māori music but also broadens the conceptual tools of ethnomusicology, demonstrating that emotion and cosmology are as valid as mathematics in organising sound.

8.4 Global Modal Systems

At a global level, the Māori case reinforces Daniélou’s argument that equal temperament is an anomaly. When we compare Māori modes to Indian shruti, Persian dastgāh, and Chinese tonal cycles, a universal principle emerges: intonation follows affect, and affect is aligned with cosmic order.

Equal temperament’s abstraction of pitch into uniform steps is historically specific, not universal. Māori music therefore belongs not on the periphery of theory but at the centre of a re-imagined global history of modal expression.

8.5 Contemporary Creative Practice

Finally, this perspective offers new possibilities for composition, performance, and intercultural dialogue. Musicians seeking to revitalise Māori traditions or to engage in cross-cultural work can treat affective intonation as a creative resource. Composers might experiment with modal frames derived from Māori affective categories; performers might design graphic scores that combine koru-based contour with Persian-style interval annotations. Such work could bring Māori modes into conversation with other global traditions while maintaining their distinct identity.

Conclusion

The argument of this essay has been to reframe Māori music not as “microtonal” in the Western sense but as a system of affective intonation.

By tracing uneven intervals to embodied emotional states — grief, anger, compassion, mockery — and situating these within ritual and cosmological cycles, we have seen that Māori practice is a modal system in its own right, comparable to Indian śruti, Persian dastgāh, and Chinese tonal cosmology.

Chapter 1 established the limits of equal temperament, drawing on Daniélou’s critique of its erasure of expressive nuance. Chapter 2 examined Māori traditions directly, showing how uneven intervals constitute affective codes that can be understood as modal frames. Chapter 3 placed this principle in global perspective, comparing it to Indian and Persian systems as well as Western performance practices such as method acting.

Chapter 4 introduced Daniélou’s śruti chart as a comparative model, while Chapter 5 mapped Persian interval values onto Māori affective modes, providing a framework for those who seek numerical description. Chapter 6 situated Māori practice within a broader Polynesian context, showing that intonation is not only affective but also cosmic, aligned with lunar calendars and star risings.

Chapter 7 proposed a culturally resonant notational system, moving beyond staff notation to graphic contours rooted in Māori symbolism. Chapter 8 drew out the implications of this approach for pedagogy, ethnomusicology, and decolonising analysis.

Taken together, these chapters point to a central insight: affect is the generative code of intonation.

Māori music, like many modal systems around the world, encodes emotion and cosmology directly into sound. Equal temperament is revealed not as the universal standard but as an historical anomaly that obscures these correspondences.

A rigorous theory of Māori music must therefore abandon the language of microtonality and embrace a framework in which uneven intervals are understood as affective modes, inseparable from ritual, body, and cosmos.

Such a theory not only does justice to Māori musical traditions but also contributes to the wider comparative study of music. It demonstrates that global systems of modal expression share a common logic: intonation follows affect, and affect aligns with the cycles of nature and the cosmos. By placing Māori music within this universal framework, we hope to open the way for both renewed scholarship and revitalised practice. Bibliography

Thanks to Dr. Michael Brown and the National Library of New Zealand.

Primary Sources & Core Ethnomusicology

Daniélou, Alain. Music and the Power of Sound: The Influence of Tuning and Interval on Consciousness. Revised edition. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1995.

Farhat, Hormoz. The Dastgāh Concept in Persian Music. Cambridge Studies in Ethnomusicology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

McLean, Mervyn. “A New Method of Melodic Interval Analysis as Applied to Māori Chant.” Ethnomusicology 10, no. 2 (1966): 174–190.

McLean, Mervyn, and Margaret Orbell. Traditional Songs of the Māori. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1975.

Tatar, Elizabeth. Nineteenth-Century Hawaiian Chant. Pacific Monograph Series No. 6. Pacific Islands Studies Program, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1981.

Stillman, Amy Kuʻuleialoha. Nā Mele Hula: A Bibliography of Hawaiian Hula Chants. Mānoa: University of Hawaiʻi, 1996.

Comparative & Supporting Literature

Donaghy, Keola. “He Ahupuaʻa Ke Mele: The Ahupuaʻa Land Division as a Conceptual Metaphor for Hawaiian Language Composition and Vocal Performance.” Ethnomusicology Review 18 (2013).

Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. “Mōteatea – Traditional Māori Songs.” Updated 2013.

Mithen, Steven. 2005. The Singing Neanderthal: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Trevarthen, Colwyn. 1999. “Musicality and the Intrinsic Motive Pulse: Evidence from Human Psychobiology and Infant Communication.” Musicae Scientiae, Special Issue 1999–2000: 155–215.

Comments